I was recently looking through old journals and was reminded that, for a period of a few years, in addition to marking time with the date of the Gregorian calendar, I also wrote out the raw total of days I’d lived. For example, beside the date July 15, 2012 is the number 8,953; I was twenty-four years, six months, and four days old. Over the next few years, I’d pick up this practice intermittently. 8,953-9,210; 9,545-9,846; and a few one offs (10,013, 12,274) on days when I suppose I felt the need for the grounding knowledge of just how many days my body had been traversing this planet.

That practice of counting gave me a feeling of continuity with my own past. It’s somehow a plain truth that this simple, clear stream of linear being contains all the tensions, contradictions, and multiplicities of my life. In those numbers are all my past selves, the life I lived and all the ghost lives I dreamed of living had I made different choices along the way.

I find this way of counting time powerful and beautiful—a capture of something utterly unfathomable, something sacred, in the quiet rise of numbers upward.

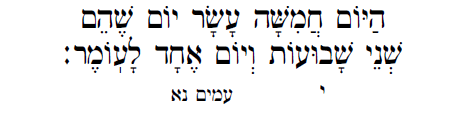

The Jewish wisdom of counting The Omer

In the Jewish calendar, right now we’re in the period between Passover—the holiday when we tell the story of the Israelites freedom from slavery in Mitzrayim/Egypt or “the narrow place” imagining ourselves making the very same trek—and Shavuot, the holiday on which we celebrate the mythical giving of the Torah at Sinai alongside the spring harvest. We call this interregnum “The Omer,” (omer meaning “sheaf of grain” so we can imagine we are counting up the abundance of the harvest) and we count each day of it. Forty-nine days in total.

Among the many discussions and legends about counting The Omer, I’m drawn to three dimensions: the material, the spiritual, and the mystical.

First, the material. What does this period mean to our bodies? What do we gain by so intentionally counting each day?

As an agricultural practice in which we are consciously marking time on our way toward the spring harvest, I believe The Omer reminds us daily to bring our attention to the rhythms of the land as it reemerges from its winter desiccation. We count a day of The Omer and see that on this day, the light lingers a little longer, a few more seedlings have sprouted, the trees grow more fulsome with leaves and blooming flowers, birdsong from those returning from their migrations crescendoes. We are Earth beings in these bodies, we remember, and like the Earth, we too experience rebirth every year, one that grows incrementally day by day.

By spiritual, I am thinking of the unseen, the undercurrents of living that influence our deeper sense of meaning, belonging, significance. This, I believe, is counting as part of the narrative of our ancestors, the journey from liberation to revelation. When the Israelites escaped slavery in Egypt, were they truly free as soon as the shackles were off? The counting of The Omer suggests they were not, that it took time and conscientious attention to each day of being free before they were ready to receive the revelation of Torah at Mount Sinai. And what is Torah? (Or more aptly for this Substack, what is T(a)orah?) I believe it is the charge to be a blessing, and then the tools of investigation and discourse to determine how best to do so. And so when we count The Omer, each day becomes an opportunity to ask: What shackles—mental, emotional, habitual—have I not thrown off? What wisdom will I need to receive and execute the charge to be a blessing? With every day we count, we remember that transformation is an ongoing, iterative process.

In the mystical tradition, Kabbalists mapped The Omer onto the sefirot, the seven divine attributes through which the energy of the Oneness flows into our world. Each week represents one of the sefirot as does each day, and so every count represents a unique combination of these attributes—

chesed (loving-kindness),

gevurah (strength/judgment),

tiferet (beauty/harmony),

netzach (endurance/persistence),

hod (humility and gratitude),

yesod (connectivity and intimacy),

malchut (majesty and wholeness).

This framework turns the counting of days into a mystical practice of focusing and directing the flow of divinity through us. For example, when we count "Today is the 23rd day, which is malchut within netzach (wholeness within endurance)," we can bring our attention to how we can stay whole within ourselves even through the most trying times. This is not a count of the calendar so much as a training regimen for sacred becoming.

This year’s Omer

We count The Omer this year against the backdrop of a number of difficult counts happening in the world. To name the ones on my radar:

Days of the remaining hostages held in captivity (569)

Days of devastation and death in Gaza (568)

Days of the invasion of Ukraine (1,526)

Days of the illiberal and increasingly authoritarian Trump administration (99)

Days since the disappearances of college students and migrants in the US that haunt our collective conscience (51-1?)

These counts mark pain and suffering. They are testaments of witness. This type of counting also has tradition in The Omer as the Talmud tells that 24,000 of Rabbi Akiva’s students died of a plague during The Omer because they did not treat each other with respect. Such measurement of time feels unbearable, so full of doom and despair.

And yet, I’m thinking of something I read from Jay Michaelson last week in his newsletter Both/And. Discussing the complicated duality of this moment in which there is so much pain to witness right in front of us while there are still wonderful moments in his personal life, Michaelson writes—

These are nested oscillations. Back and forth, from spirituality to justice, from distraction to dread, from emptiness to form, from a long term unknowing to an immediate knowing, from beauty to brokenness, from turning toward God to turning toward human beings. Ratzo v’Shov, in the Jewish metaphor: running and returning.

I’m thinking of this because as the painful counts above increase each day, in my personal life I’m holding a counteracting count of absolute love—the days my daughter has been alive. Today, on the 15th day of The Omer, that count is eight.

Eight days of new breath—fast and slow as her lungs grow into their living rhythm—eight days of little hands conducting orchestras in the air, eight days of eyes opening alert and aware and taking in light for the first time. Like the Omer's agricultural count, every day she grows in the smallest increments—a stronger neck, more food, exploring the muscles in her face. She too has come from the narrow place of the womb into the expansive revelation of breathing air. Like the mapping of divine attributes, each day represents a new iteration of the mystical combinations of divinity that flow through her as she becomes.

Even as I write this, I fear that it may be almost monstrously selfish to be so overcome with hope and joy by counting the days of my daughter’s life—have not all the souls harmed by the abuses of today counts of their lives? Of course they do. And yet I learn again the preciousness of a life in watching my daughter grow, and from that building block, I find greater depth to my yearning for the end of pain for all the precious lives suffering in this moment.

In the counting of The Omer, all these joys and sorrows are held together in the container of days. The ancient, the abundant, the excruciatingly painful, the unspeakably joyful, the collective, the deeply personal.

We count and we view glimpses of time’s sacred container and our attention is pulled today, to this present, to all its multitudes of beauty and ugliness and we say:

Today is 15 days, which are two weeks and one day, of The Omer.

You really should write a book

Not monstrously selfish but the very opposite. In your love for your daughter and in the joy you are taking in her days you pour goodness into the world and into your readers’ lives.