On Disintegration and Return (part 3)

Practicing the Cycle

This is the third and final post in a three part series; you can find the first post here, and the second post here.

We experience disintegrations on scales large and small—projects end, hearts break, we have health scares and calamities, we lose loved ones, global pandemics invade our personal worlds, great conflicts arise and destabilize us—and we feel their effects—an arresting of agency, a tumble out of our own skin such that the very ability to make decisions feels like it’s gone, like walking down a New York City sidewalk and having one of those metal cellar doors break open under our feet. The Crash begins and we may shrivel up, freeze, shake, feel lost, or become loafs in time. All these reactions make perfect sense when form as we know it unravels.

And then, in one way or another, the return—on the positive end of the spectrum of return, a new project starts, we fall in love, ingenuity creates vaccines, new leaders and empowered communal structures emerge; or on the more distressing end of the spectrum of return, we hide ourselves with numbing agents like excessive substance use or bingeing TV (my personal poison), we pick fights online and in person and put ourselves into an unending and exhausting fight or flight disposition, we see powerful and malevolent forces driven by greed, hate, and delusion step into the void to crush the already downtrodden and exert their will over as many and as much as they can.

Given the threat of the distressing possibilities of a bad return, it's tempting to say, "we should do everything in our power to avoid disintegration." But we can't control disintegration, and what’s more, I think we actually need it. The book of Kohelet/Ecclesiastes describes the power and inevitability of disintegration in beautiful clarity. The voice of the writer (traditionally attributed to King Solomon, although I like to think it was a daughter of Solomon using his name as it’s hard to imagine wisdom this rich not coming from a woman) guides us through an examination of life’s wisdom, pleasure, work, and wealth—finding each ultimately as fleeting as breath. "A time to break down, and a time to build up," Kohelet reminds us, "a time to weep, and a time to laugh, a time to mourn, and a time to dance." If we appreciate the stunning transience of everything, then we might come to appreciate disintegration as not just inevitable but essential.

In the first post of this series, I wrote about Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” a formative book for me in my early twenties. In that book, Kerouac beautifully renders the journey of disintegration of his self as he’s known it over the course of a period of time in which he is rootless, moving, able to allow himself the freedom to follow inspiration and whim in new directions. As I mentioned, he ends the book with the character based on him, Sal Paradise, “settling down” into marriage and family life. But Kerouac’s real life didn’t stay in that return. It re-cycled to disintegration, as a life will do. Except, tragically, Kerouac lost his ability to appreciate the disintegration, and his returns became more self-destructive—he abused alcohol, he hurt his loved ones, he disowned his friends. In “After Me, the Deluge,” the final essay he wrote before he died of cirrhosis of the liver at age 47, he veers into bitter disavowals of the literary and cultural worlds he’d become associated with and ultimately lashes out into rote antisemitism.

There be many a’ tripping snag and caging trap on this cyclical path we walk. So how do we navigate the cycles and avoid the fate of Kerouac and so many others?

I don’t have answers, only some notions of practice.

A Taoist insight for being in disintegration

Chapter 19 of the Tao ends with these lines:

Look at plain silk; hold uncarved wood.

The self dwindles; desires fade.

I think one of the keys during a disintegration to being a ghost like Kerouac describes—open to possibilities, free to see the unfolding road ahead—is to look at it as plain silk, to hold it as uncarved wood. That is to say, not only to experience it abstractly as something that exists external to us, but as a physical, natural part of creation, as real as silk or wood in the wild. If we become passively receptive to disintegrations as naturally occurring elements of existence that we can bear witness to, if we can allow ourselves not to strive to avoid it or get through it faster, I think this increases the likelihood that the next return will be one of renewal.

This notion of passivity might seem to fly in the face of the great majority of popular self help works that, in one way or another, try to advise a person in how to work to regain control of their lives.

Yes, it really might seem to do that.

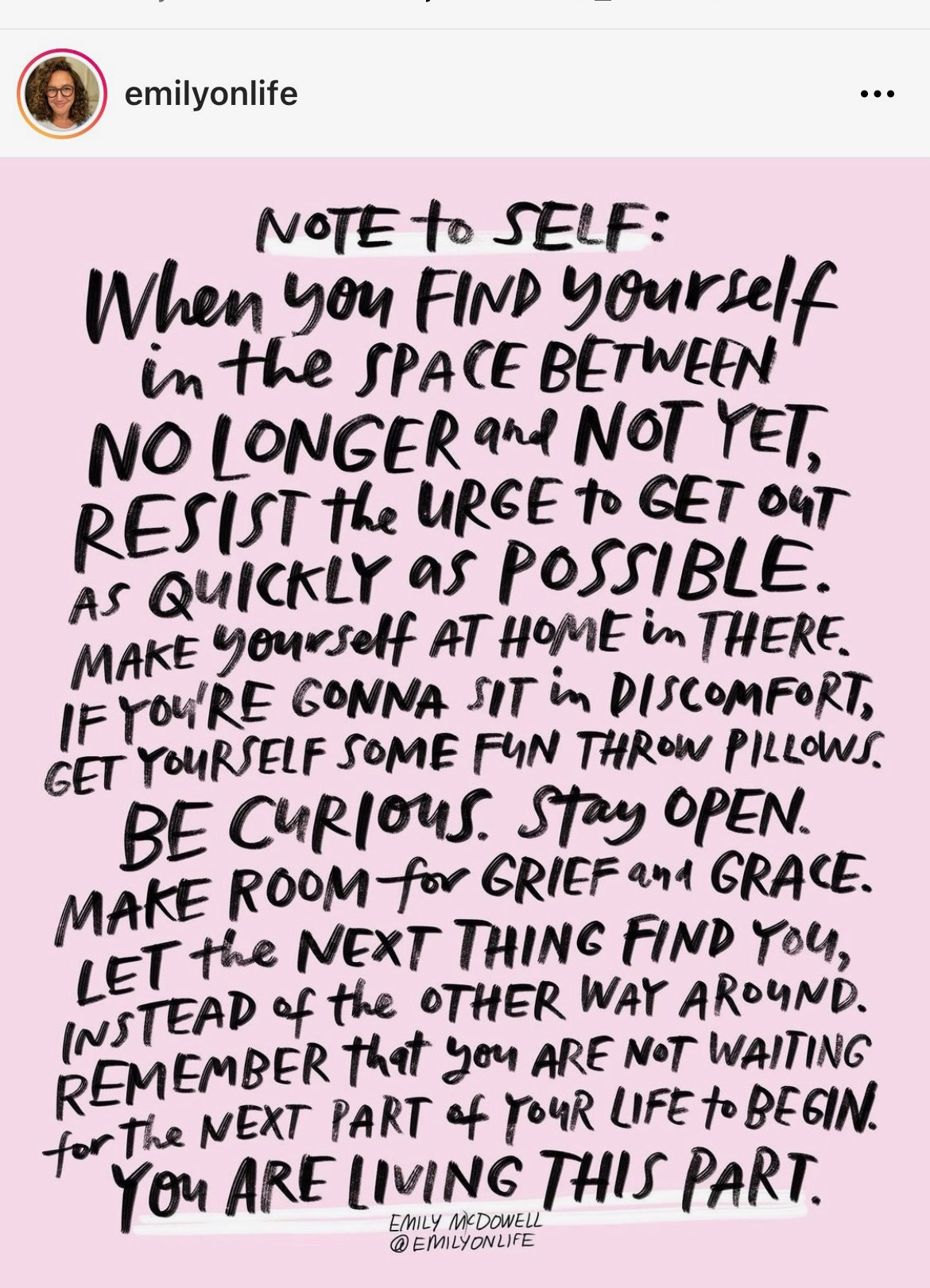

Here’s a good take I came across:

So what to do? Some practices

Perhaps to the Taoist, that’s the end of the discussion. But this is Living T(a)orah, so there are some gentle practices I’ve pulled from the burgeoning world of Living Torah Jewish life and started to apply in my life. These practices help me remember to be present for my disintegrations and returns, to treat them like silk and wood, and to try to channel the energy they produce towards renewals of growth.

I’m going to describe three practices below that I think of as my “anchor practices.” Out on the high seas, a ship will throw its anchor when the chaos of the roiling water becomes so intense as to be destructive, and, just as importantly, the sailors aboard the ship will have all regularly practiced in calm waters how to throw that anchor effectively. Which is to say that doing anchor practices regularly, literally practicing them, is the best way to determine when to be passive towards life’s disintegrations and returns and when to lean into a more active attempt to shape them.

My colleague and friend, Ayalon Eliach, often points out that, yes, having the containers of regular practices is great, but it also matters what fills those containers. An anchor can, after all, lodge so tight into a singular place that a ship can’t move on the water anymore, and such a paralysis can be as dangerous to a ship as any mighty squall. I believe that an over reliance on practices that emphasize identity and label anchors—for example, thinking during a disintegration, “I am an X [insert immutable identity/label here], therefore my practice is to return always to this spot where I, as an X, know the answer exists”—is just such a danger: it can ossify a person in their ways, create a hard binary when a soft spectrum will do.

With that in mind, here, in brief, are my (current) three anchor practices that I do regularly so that when my own disintegrations occur, and when larger societal disintegrations occur, I’m ready to return renewed, with creativity, a shov toward love.

Bedtime sh’ma—The sh’ma is often pointed to as the core prayer of Jewish liturgy, and indeed, the Talmud begins with a discussion of “until what time” a person can say it at night. The most common translation in prayerbooks you’ll see of this prayer goes like this: “Hear o’ Israel, the Lord Our God, the Lord is One,” but that translation stopped sitting well with me about a decade ago, when I started this practice. Instead, re-engaging with the Hebrew and its grammar, I began translating it like this:

Sh’ma—Listen!

yisrael—You, wrestler with the divine

yhvh eloheinu yhvh—The divinity, our divinity, the divinity

echad—Is Oneness.

The instruction and insight of this translation feel better to me—the pause after the strong admonition to “Listen!”, the acknowledgment of all the distinctions and complexities of daily life in that phrase “wrestler with the divine,” the call to a divinity that exists in itself and is also ours, the reminder that beneath these daily wrestlings is the unspeakable Oneness.

Recently, I made a new change to how I say the sh’ma each night. During this year’s Jewish High Holidays, my wife and I attended services at Lab/Shul in Manhattan led by Amichai Lau Lavie. There, Amichai and the Lab/Shul team introduced us to a practice of rearranging the letters of the name of the divinity in Hebrew, no longer pronouncing the name as “adonai” which literally translates to “masculine lord” but rather as “havaya,” which is a form of the verb that means “to be,” and connotes a continuing and unending being-ness. Now, every night, I say the sh’ma before bed this way: Sh’ma (long pause) yisrael, havaya eloheinu havaya, echad.Morning meditation and gratitude—Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, the Piaseczner Rebbe, who taught in the Warsaw Ghetto and died in the gas chambers of Treblinka, used to teach a meditation technique he called “quieting.” It’s quite similar to Buddhist Vipassana meditation. In this type of meditation, the practice is one of mindfulness—observation, without judgment, of thought.

Rabbi Shapira taught,“…first a person should watch his thoughts for a short while, that is, what he is thinking. He will slowly feel that the mind is emptying; his thoughts are slowing a bit from their habitual flow. […] One repeats this several times, but not forcefully. The whole point here is to quiet one’s thoughts.”

My goal is to do this for 30 minutes every morning before 7:30am (I’m an early riser). The way I learned to meditate (from teachers at Or HaLev) is to pick an anchor like my breath, or my butt in the chair, or my feet on the ground, or (my usual anchor of choice) the low sound of my apartment building’s general hum in my ears, and then, whenever my thoughts drift off as they inevitably do—some common areas of thought for me include future planning, relitigating old arguments, fantasizing about what could have been had things gone differently, or what could be if things go a certain way—noticing those thoughts, and returning my awareness to my anchor. In this way, I practice the simple, profound act of noticing.

In Vipassana meditation, the passivity continues and insights emerge during mindfulness practice. However, in Rabbi Shapira’s tradition, one can very gently request insight. He said,“Afterwards [a person] can request what [they] require in whatever aspect of character development [they] need to perfect whether the strengthening of faith, love or awe…”

As part of my morning practice, I cultivate gratitude. This is inspired by the Jewish wisdom tradition to start one’s morning with the prayer, “Modeh/ah ani lefanecha, melech chai v’kayam”/Grateful am I before you, living and eternal king.” At some point in my meditation each morning, I chant these words, though, as with the change from adonai to havaya in the sh’ma, I substitute the word ruach/spirit for melech/king.

Shabbat—A close friend of mine used to take “undays” in college when he felt overwhelmed by life. On those days, he would skip all his classes, lie around in a bathrobe, and try to gain respite from the relentless tasks of actively living a day. An “unday” in my friend’s parlance was a choice, an intentional rest, an emergency brake to pull in the midst of existential crisis.

How amazing to discover that such 'undays' are built into Jewish tradition. A full day in which to refrain from work. But Shabbat differs from an 'unday' in crucial ways—it's not an emergency response but a regular practice, not a withdrawal from crisis but an invitation to weekly renewal. When we observe Shabbat, we're actually practicing a form of controlled disintegration: letting go of our usual structures, stepping away from our tools of control, and allowing ourselves to simply be.

This regular practice of intentionally and actively letting go makes us better equipped to handle those moments when something beyond our control pries us our fingers off the levers. Shabbat, then, is more than just rest—it’s a weekly day-long rehearsal of disintegration and return.

Last thing: the power of others

I recently attended a Zoom gathering of about twenty five people to sit in meditation together. Most of the time, I sit alone in my apartment, and I’ve tended to believe that, ultimately, there’s not much difference between sitting alone and sitting with others—silence is silence after all. But on this call, even though I was still physically alone in my apartment, I experienced a profound realization. Silence is not just silence, by which I mean, silence is not an absence but a presence. With all those people also holding silence with me, there actually was more silence, which meant more space for my mind to roam, more time to skip through. That we were sharing this silence became its own powerful expression of unity among our group, a service we were all providing not only to ourselves but to each other.

Which is to say, all of these practices are better with people. Disintegrations are mitigated with people, returns more empowering with people. The title of a book from the 60s on shtetl life I once saw when I worked in a secondhand bookshop in New Orleans keeps coming to mind. “Life is with People,” it was called. And yes, it most certainly is.

This is beautiful and what a translation of Shema! I’d been using one that moves in this direction but not channeled as powerfully or clearly as this. Thank you.

Are you familiar with the Sefer Yetzirah on disintegration and return—ratzo v’shov; im ratz libecha shuv lamakom?