On Texts

And how Jewish Wisdom's sacred literature is an invitation to create more

This is the third post in a four part series. Here’s the first post, On Fear, and the second, On Religion.

For a few minutes, let's go back to tenth grade geometry. Imagine you’re a two-dimensional being living in Flatland, and a three-dimensional sphere passes through your world; what do you see? Not the sphere itself, but its cross-sections visible in your dimension—circles of varying sizes that appear, grow, shrink, and disappear. You might sense there's something more, something larger and mysterious and enchanting, but you can only describe what this dimension allows you to perceive.

What is sacred Text?

One of my mentors and teachers, Dan Libenson1, will often talk about the "True Torah" being the "Torah of the heart." Don’t mistake his meaning though; he isn’t arguing for a wishy-washy “Torah” primarily made of feelings or vibes. Rather, he’s making the case that while Torah is something real, something that exists, its True Reality is beyond our corporeal comprehension; however it makes itself best known to us, he explains, by the impression it makes on our hearts.

The way he describes it, the "True Torah" might be understood as a fourth dimensional Torah. It comes to us like the three dimensional sphere comes to the two dimensional shapes in Flatland. We can see it only within the dimension in which we exist, though its reality is so much more, and what lies beyond our material senses of it is felt in our hearts. We translate what we sense and feel into words legible to others in our dimension.

Thus we can understand that our ancestors roaming the lands of ancient Mesopotamia and the Land of Canaan, looking after their herds and settling to plant crops, first told each other the stories of their ancestors—Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Rachel and Leah—and of the Israelite family going down to Egypt, becoming a great nation in exile, only to be enslaved. They told of the complicated hero Moses who led the people out, and of the attempt to build a righteous and just civilization in their land, with all the triumphs and failures that ensued. These stories, evocative of the Truth but spoken in language they could comprehend, eventually were written down and became what is traditionally called the "written Torah"—the five books of Moses, the Book of Judges, the Prophets, the Books of Kings, the Books of Daniel and Esther, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Psalms.

As history progressed, the stories continued—the tales and arguments of the Rabbis, the Roman exile, the revolution that transformed a Temple-based religion of pilgrimages and sacrifices into one of prayer and micro-communities dispersed around the world—and those too were written down in what became the Talmud.

Dan's point is simple but revolutionary: the distinction between the "written Torah" and the "oral Torah" made by the early Rabbis of the Talmud in order to justify their own writing as equally canonical to those earlier Texts is no distinction at all. There is only oral Torah that gets written down. And while such oral Torah is only ever an echo of the True Torah that exists in a dimension beyond us, when it is written, it becomes something powerfully different from oral Torah—written Torah is not just a recording, it is an editing, a revising, an attempt at harmonizing contradictions of myths into the dynamic tensions of writing, a message for the future.

Such writings are what we call Text. And if this is true—if all our sacred writings are merely approximations, cross-sections of something infinitely larger—then how do we approach them? How do we read not just the words on the page, but through the shadows they cast towards that greater Truth that moves through dimensions we can only begin to imagine?

Text as a window

I believe the primary value of reading and studying sacred Texts is that they can provide us a two-way window for interaction with our ancestors. In one direction, we look through the window to see how our ancestors understood their own world. In the second direction, our ancestors peer back at us and we glimpse how they might view our own circumstances, gleaning their wisdom to deepen ourselves and act better in the world. When we can both see our ancestors and their world and feel them seeing into ours, Text study becomes nothing short of magical.

To read Text in this way is to first acknowledge it as human-written, as the expression of the hearts and fragmented observations of the True Torah from times past. It is to read Text as the literature of the ancient world, which, in myriad important ways, was not so different from our world. The sun and moon still shone back then, oceans were still powerful and forests still mighty, people could still be greedy and petty and hateful, and also kind and warm and heroically peace-seeking.

When we read these Texts and peer through the window they provide into their world, we see how they made sense of disintegration and return, of power and powerlessness, of cynicism and skepticism, of yearning and brokenness. We witness their struggles with the same fundamental questions that occupy us: How do we live justly? How do we love well? How do we find meaning in a confusing world with so much suffering? How do we build communities that thrive?

And the window works the other way too, though only if we let it. Through their words, our ancestors can peer into our world, whispering wisdom across the millennia and centuries. They see our struggles with rapidly progressing technology and spiritual and social alienation, our grappling with inequality and climate change, our societal lurches toward extremism, our searches for authentic selves, intimate relationship, and transcendent purpose. And from their vantage point—informed by their own encounters with empire and exile, abundance and scarcity, faith and doubt—they offer us counsel.

This is why we return again and again to these ancient voices. Not because they provide us with a rulebook for modern life, but because they’ve walked similar paths through the wilderness of human existence. In their stories of failure and resilience, their arguments about justice and mercy, their songs of lament and celebration, we hear the whispered wisdom of those who have faced what we face, felt what we feel, and found ways forward that we might not have imagined on our own.

Study as sacred conversation

This approach to Text as multidimensional window across time is practiced in the radical pedagogy of SVARA2, a queer yeshiva in Chicago. In SVARA’s pedagogy, students and teachers must bring to the Text not only our analytical minds but our full selves—our hopes and fears, our experiences of joy and sorrow, our questions about how to live. We must be willing to be surprised, challenged, even transformed by what we encounter. We must allow our own moral intuition to provoke the voices and the Text, and to be provoked by those voices in turn.

This kind of generous attention to the Text also means reading with sophistication about the contexts from which these Texts emerged. We honor our ancestors not by taking their words as literal prescriptions for twenty-first century life, but by understanding the circumstances that shaped their insights and considering how those insights might translate into wisdom for our own circumstances. We read with historical awareness, cultural sensitivity, and an appreciation for the complexity of translation—not just of words from one language to another, but of wisdom from one generation to another.

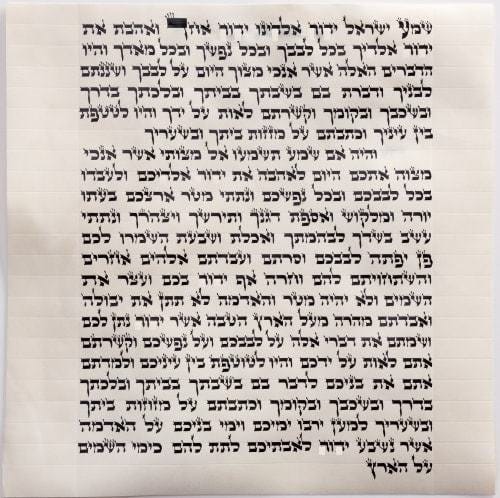

An example: When do we say the Sh'ma?

Let’s see what this might look like in practice. The Mishnah—from the root meaning “repetition,” implying “The Second Torah,” the foundational collection of Rabbinic teachings that became the first core writings of the Talmud—opens with this question: "From what time may one recite the Sh'ma in the evening?" What follows is a detailed discussion of the precise moments when this central prayer should be said, with multiple rabbis offering different opinions about whether it's when the priests eat their terumah (the portion gifted by the people to the priests), or when the stars appear, or when the poor man comes home to eat his bread with salt.

A conventional reading might approach this Text as instruction: When exactly should I say the evening Sh'ma? But reading through our bi-directional window reveals something far richer about what our ancestors held sacred.

First, notice what they chose to begin with. Of all the questions they could have opened their great compilation with, they started here—with the Sh'ma. This tells us that the rabbis considered this prayer so fundamental to Jewish life that its proper recitation deserved the very first discussion. The Sh'ma, with its instruction: “Listen! Divine struggler, divinity, our divinity, divinity is Oneness” and its subsequent call to love this divinity with all our heart, soul, and might, was not just another prayer but the cornerstone of daily spiritual practice.

And look how they approach this cornerstone: not with a single, definitive answer, but with careful attention to the rhythms of ordinary life. When do the priests eat? When do the stars emerge? When does the working person return home for their simple meal? Our ancestors were teaching us that sacred time is not separate from the texture of daily existence—it emerges from careful attention to the movements of our ordinary world.

There's something beautiful about their willingness to luxuriate in these details. They could have simply said "at nightfall" and moved on. Instead, they invite us to notice the subtle hues of twilight, the different ways people experience the transition from day to night. A priest's schedule differs from a laborer's; the rich man's evening looks different from the poor man's.

(My favorite dispute over such details comes in the immediate next section, when the rabbis discuss the time to say the morning Sh’ma—

From when does one recite Shema in the morning? From when a person can distinguish between sky-blue [tekhelet] and white.

Rabbi Eliezer says: From when one can distinguish between sky-blue and leek-green.

Is the right time when one can see the sky turning white after being sky-blue, or when it’s moving from sky-blue to leek-green? Let us sit and watch the sky and ponder.)

Perhaps most remarkably, they preserve multiple opinions rather than forcing consensus. An unnamed opinion (usually thought to be Yehuda HaNasi, the compiler of the Mishnah) says one thing, and Rabbi Eliezer says another, and instead of declaring one winner, the Text holds space for both voices. Perhaps we can surmise that these ancestors understood that the greater Truth to which they were striving could only be seen in those splintered gradations, cross-sections of the sphere, and so they took pains to record the ongoing conversation between different perspectives, honoring the different experiences of the greater Truth.

What wisdom these ancient voices whisper to us.

In our age of rigidity, polarization, fear, and confusion, they model how to hold disagreement within community rather than allowing it to fracture relationships. In our time of rushing through days without pause, they invite us to notice the subtle transitions that mark our hours. In our era of spiritual seeking, they remind us that the path to transcendence runs directly through attention to the ordinary moments of our lives. And in our search for meaning, they suggest that some practices are so essential to human flourishing that they deserve our most careful, ongoing attention—not because they provide easy answers, but because they keep alive the questions that matter most.

Is there space for new sacred Text?

To this question, I offer an unambiguous yes! Not only is there space, I believe we're called to do it. It is our responsibility to both our descendants and our ancestors to continue the attempt to write down for future generations what our observations—rooted and informed by the writings of the past—and our hearts conceive to be the new approximations of the True Torah.

If Dan Libenson is right that all Torah is oral Torah that gets written down, and if all written Torah is merely our best attempt to translate the impressions of transcendent Truth on our hearts into words legible in our dimension, then the project can never be finished. Each generation encounters new shadows of that fourth-dimensional reality, sees new cross-sections of the sphere passing through our Flatland. We have access to observations that our ancestors could not have made—about the cosmos and consciousness, about human dignity and planetary interconnectedness, about trauma and healing, about the possibilities and perils of technology.

We also live with hearts shaped by new experiences of history. We know things about what it means to be human that previous generations could not have known, just as they knew things that we’ve forgotten or never learned. Our senses of Truth will differ from theirs—hopefully progressing toward a better world, though sometimes not, but always different. And such difference matters.

Our descendants will need to hear from us about how we made sense of this agitating and confusing moment. They will need our stories of failure and resilience, our arguments about justice and mercy, our songs of lament and celebration. They will need to know what practices we found essential for human flourishing, what questions we thought deserved ongoing attention, what disagreements we held within our communities without allowing them to destroy our relationships.

Part of our noble pursuit in this life is to serve as caretakers of the window. Just as our ancestors peer through their words into our world to offer counsel, we must peer through our words into the world of our descendants to offer them what wisdom we can.

The True Torah continues to cast new shadows on new hearts. Our job is to notice them, to translate them as best we can, and to write them down. Such writings, too, are what we call Text.

Up next: a final post in this series about what precedes Text, what we've called here oral Torah, what I call Myth.

Cited or referenced:

Past Living T(a)orah Posts:

Dan is the founder of Judaism Unbound and co-host of its eponymous podcast; the President of Lippman Kanfer Foundation for Living Torah (where I work with him), co-host with Benay Lappe of The Oral Talmud streaming show, and general Renaissance futurist of Jewish life. I’ve written about Dan multiple times in this newsletter.

SVARA was founded by Benay Lappe to be “traditionally radical” and the first ever queer yeshiva. I’ve written about Benay multiple times in this newsletter.

I enjoyed reading this one Daniel. It was very insightful.